Curricular Experimentation

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vernelle Harris Hall |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

“We taught the whole child while still setting high standards for our students. If a child needed shoes, we would find a way to get them. If a child needed clothes, we would find them. School at that time was unequal but we found a way.” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Beulah M. Carter |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

“The project method was important at Staley High School. In fact, there was ‘a project day’ for the entire county when school children would come together and present their projects.” Beulah M. Carter |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

One dimension of curricular planning that permeated the Secondary School Study was the effort to correlate the traditional subjects into a core curriculum, i.e., to draw out connections among the individual subjects as they were taught in their respective classes. The content was decided through a combination of teacher-pupil planning and teachers’ analysis of students’ needs and interests. While the “project method,” a common progressive education instructional practice of the time, was employed in many classrooms, the curriculum still remained focused upon academic knowledge. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

N. Carolyn Thompson |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Addie Rose Owens |

“Yes, there was student-pupil planning in the progressive tradition. Staley teachers adapted the formal curriculum due to the fact that they veered in order to meet the needs of the child. General health was a good example (and TB was feared). Teachers would begin addressing issues of health when they saw social problems.”

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

“As an elementary school teacher (beginning in 1941), we had very close contact with the Staley High School teachers, especially since so many of them came from McCoy Hill School. I attended Albany Normal School. When I returned to teach, we used the ‘project method’ and other progressive education methods that drew on the interests of the students. We knew that if we found out the children’s interests, they could be taught.” |

Vernelle Harris Hall, 3rd grade teacher at McCoy Hill School, 1941-1949 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

graduates from the Staley High School Class of 1944 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

During the time of the Secondary School Study, the Georgia State Department was encouraging schools to develop an integrated type of program based on seven persistent problems of living (inspired by Hilda Taba and Robert Havighurst). Staley High faculty planned an integrated program where science attended to the persistent problems of health and, at the eighth grade level, sample units were developed on three specific “persistent problems”: health, citizenship, and earning a living. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

“We used a Problems of Living curriculum and taught more than what was in the books. Students had many questions about life at that time—there was much more information needed than mere facts about life, food, and shelter.” Alpha Hines Westbrook, the Staley High School vocational education teacher during the time of the Secondary School Study |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

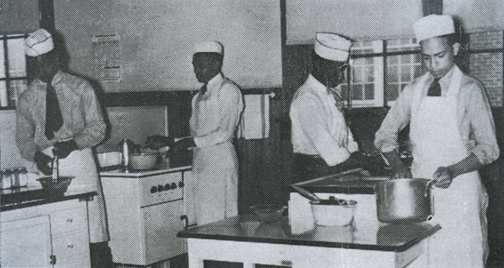

from Tri-County News, April 1942:

The historical mission of black education at the secondary school level is often described as the tension between a college preparatory course of study and a more occupational-vocational curriculum, a false dichotomy established by the emblematic beliefs of W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington. Participating Secondary School Study sites often configured their curricula to bring together all students and to permit the core courses to serve as an occasion to define community. Further, traditional "vocational topics" such as homemaking were expanded to address general education topics of health and social action (in the classic progressive education tradition of the 1930s with projects focused on community welfare). Specialized courses allowed students to pursue specific academic and vocational interests, yet the core courses brought all the students together in homogenous groupings. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Leroy Williams |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

an institutional member of the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience

curator@museumofeducation.info