The Dudley High School Building “In most of the Southern states, services to black schools have been confined largely to the program of increasing and improving physical facilities. This effort should continue but, at the same time, a program for intelligent use of available facilities should be well established.” |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

“We had such a beautiful school. The building was so lovely and distinguished. The structure showed the significance of what was going on in the classrooms.” |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

Among the participating sites of the Secondary School Study, Greensboro is one of the few cities where its leaders provided “somewhat equal” support for the building of its high schools for black and white students. When the “High School for Negroes” was opened in 1929, its total cost was substantially less than what had been spent on “the million dollar school,” the Senior High School for Whites (now known as Grimsley High School). Yet, the difference in cost between the two schools, as noted in the National Register of Historic Places Registration form prepared by Jo Ann Evans Lynn, was due primarily to the size of the buildings rather than to the quality of construction. The fact that Dudley High School receive the same level of commitment as the high school for white students is quite rare during this period and is attributed to the commanding presence of Dr. John Tarpley who insisted that the construction of schools be equitable. Both schools were designed by the distinguished Greensboro architect, Charles C. Hartmann (1889-1977), known for his Beaux-Arts style. Hartmann assisted in the drafting of New York City’s Grand Central Terminal’s main lobby and later designed Greensboro’s Jefferson Standard Building and many other landmark buildings in North Carolina (including Greensboro’s F. W. Woolworth Building, site of the 1960 student sit-ins). |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

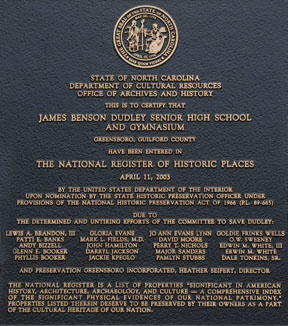

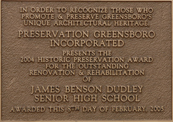

| The school, named for James Benson Dudley, the second president of North Carolina Agricultural and Mechanical College (now North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University), had been allocated over eighty acres of land. Combining Gothic Revival and Art Deco styles, Hartmann’s architectural design for Dudley High School, the first public secondary school for blacks in North Carolina, more than justified the structure’s listing in 2003 as a designated site on the National Register of Historic Places. | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

Alma Mater Foundation built, our lives will forge ahead, |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

From the 1946 Secondary School Study catalog description J. A. Tarpley, Principal

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| “Despite some progress, Greensboro’s ‘separate but equal’ black schools suffered from poor equipment and textbooks that frequently were rejects from the white schools. When Tarpley approached the Superintendent to seek improvements, he always brought two plans—one for full equalization that he knew would be turned down, and a second that would meet many of his needs even as it appeared to be a compromise in the eyes of his white superiors.” William H. Chafe, Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina, and the Black Struggle for Freedom | ||||||||||||||

an institutional member of the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience

Museumofed@gmail.com