| |

Home

|

|

| |

Books of the 20th Century Exhibition

An introduction to some publications that have shaped the field of education.

Photos by Mundo Images

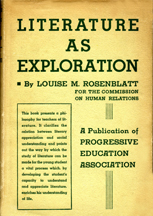

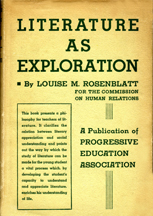

Literature as Exploration by Louise M. Rosenblatt

(New York: D. Appleton Century Co., 1938) |

|

| |

Louise M. Rosenblatt

|

|

“I doubt that any other literary critic of this century has enjoyed and suffered as sharp a contrast of powerful influence and absurd neglect as Louise Rosenblatt. . . . She has in fact been attended to by thousands of teachers and students in each generation. She has probably influenced more teachers in their ways of dealing with literature than any other critic. But the world of literary criticism and theory has only recently begun to acknowledge the relevance of her arguments.”

––Wayne Booth (1995, p. vii) |

|

|

|

|

Louise Rosenblatt’s books and theories––Literature as Exploration, The Reader, The Text, The Poem (1978), reader response theory, transactional theory––have guided generations of language arts teachers as they sought “to foster fruitful interactions or, more precisely, transactions between individual readers and individual literary texts” (p. 26). Literature as Exploration displays the reciprocal nature in the act of reading and views meaning as neither in the text nor in the reader. Her transactional theory celebrates reading as an active event.

Louise Rosenblatt, c. 1938

Reflections on Literature as Exploration by Louise M. Rosenblatt

reprinted from the Museum of Education's Books of the Century Catalog

Because I could draw on both literature and the social sciences, in 1935 I was appointed to the Commission on Human Relations, chaired by Alice Keliher and initiated by Lawrence K. Frank and a group of social scientists through a grant by the General Education Board to the Progressive Education Association. The Commission’s purpose was to publish a group of books about such topics as family relations, human development, and psychology for late high school or early college readers. My function was to help plan the books. Others, skilled in popular writing, were to do the actual writing. That gave me my first contact with the schools.

When my part of the work was done, I reflected on the difference between reading about human relations in these books and the discussions of human relations in my classes after the reading of literary works of art. The class discussions of problems in human relations arose out of what the readers had thought and felt in evoking meaning in transaction with the text, and were efforts to think rationally about such topics in an emotionally-colored context. It seemed to me that the resulting insights might be more personally-felt, perhaps more lasting, than those derived from the impersonal, scientific approach of the books we had planned. Both approaches seemed to me to be needed.

There was no provision for any Commission book on the teaching of literature. But I felt impelled to express these ideas. I went out to the country with a secretary and dictated most of the book. Recall that this was in the thirties, when both Nazism and Stalinism were powerful. I was motivated to relate all of these concerns to their role in a democracy. My work for the Commission gave me the opportunity to fuse all of these and to organize my ideas about the relation of literary experience to thinking about human relations in a democracy.

My belief in the importance of the schools in a democracy has not only evolved but also increased over the years. In 1938, democracy was being threatened by forces and ideologies from outside. Today, I believe it is again seriously threatened, this time mainly by converging forces from within. From local schools to state standards to Supreme Court cases, education has become an arena for this ideological struggle. Special interest groups have been organized to achieve domination of local school boards; topics such as methods of teaching reading or allocation of funds to research have become political issues at all levels.

My efforts to expound my theory have been fueled by the belief that it serves the purpose of education for democracy. Ultimately, if I have been concerned about methods of teaching literature, about ensuring that it should indeed be personally experienced, it is because, as Shelley said, it helps readers develop the imaginative capacity to put themselves in the place of others––a capacity essential in a democracy, where we need to rise above narrow self-interest and envision the broader human consequences of political decisions. If I have been involved with development of the ability to read critically across the whole intellectual spectrum, it is because such abilities are particularly important for citizens in a democracy.

Of course, the schools cannot do the whole job, but they are essential. We’re already overburdened as teachers, yet as citizens we need to promote and defend the social, economic, and political conditions that make it possible for us to carry on our democratic tasks in the classroom.

Louise M. Rosenblatt, Books of the Century Catalog, 2000, p. 42-43.

Craig Kridel, editor/arrayer (2000). Books of the Century Catalog (Columbia, SC: Museum of Education).

|

“One of the wonders of art is its multiplicity of powers; the literary work, even as it gives pleasure, may be fulfilling many other functions. Viewing literature in its relations to the diverse needs of human beings, this book will seek to answer the questions: ‘How can the experience and study of literature foster a sounder understanding of life and nourish the development of balanced, humane personalities?’ ‘How can the teacher minister to the love of literature, initiate his students into its delights, and at the same time further these broader aims?’”

Louise Rosenblatt, Literature as Exploration, 1938, p. v.

|

|

|

|

__ __

The Museum of Education on-site exhibition; two views

|

Preface

“The enjoyment of literature remains as ever the source from which all its other values spring. If we are to help young people to come fully into their literary heritage, of which we are the trustees, we must cleave to this sense of literature as first of all a form of art. Yet one of the wonders of art is its multiplicity of powers; the literary work, even as it gives pleasure, may be fulfilling many other functions. Viewing literature in its relations to the diverse needs of human beings, this book will seek to answer the questions: ‘How can the experience and study of literature foster a sounder understanding of life and nourish the development of balanced, humane personalities?’ ‘How can the teacher minister to the love of literature, initiate his students into its delights, and at the same time further these broader aims?’” (p. v).

Quotes

“The teacher of literature, above all, needs to keep a firm grasp on the central fact that he is seeking always to help specific human beings––not some generalized fiction called the student––to discover the pleasures and satisfactions of literature. The teacher’s job, in its fundamental terms, then, consists in furthering a fruitful interrelationship between the individual book or poem or play and the individual student. The teacher is dealing with a necessarily fluctuating and dynamic problem. His material is no less than the infinite series of possible interactions between individual minds and individual literary works” (pp. 32-33).

“Every time an individual experiences a work of art, it is, in a sense, created anew. Fundamentally, the process of understanding a work implies a recreation of it, an attempt to grasp completely all of the sensations and concepts through which the author seeks to convey the quality of his sense of life. Each of us must make a new synthesis of these elements with his own nature, but it is essential that he assimilate those elements of experience which the author has actually presented” (p. 133).

Closing Lines

“Our society needs not only to make possible the creation of great works of art; it needs also to make possible the growth of personalities sufficiently sensitive, intelligent, and humane to be capable of creative literary experience. In the pursuit of such ideals, we shall make the teaching of literature a function worthy of the humane nature of literature itself. Literary experiences will then be a potent force in the educational process of developing critically minded, emotionally liberated individuals who possess the energy and the will to create a happier way of life for themselves and for others” (p. 328).

Contents

Literature as Exploration by Louise Michelle Rosenblatt (1904–2005) ; Barnard College). New York: D. Appleton Century Co., 1938. [xiii; 340 p.; 21 cm.]

Preface

Foreword by Alice V. Keliher

I. The Province of Literature

1. The Challenge of Literature

2. The Literary Experience

II. The Human Basis of Literary Sensitivity

3. The Setting for Spontaneity

4. What the Student Brings to Literature

to return to the Books of the 20th Century Exhibition

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

__

__