Books of the 20th Century |

||||||||||||

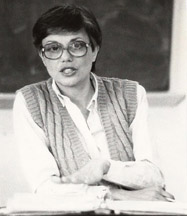

Sonia Nieto, 1987 |

Affirming Diversity: The Sociopolitical Context of Multicultural Education Reflections on the Writing of

The following narrative is adapted |

|||||||||||

Although my time as a doctoral student and early career faculty member at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst (starting in 1975) was transformative, it took some time for what I had learned and what I was thinking in those years to percolate and come to the top of my consciousness. In 1988, just before I received tenure at the University of Massachusetts, an education editor from Longman Publishers came to my office. He had come to see me because Masha Rudman, one of my colleagues in the School of Education, had suggested I had some interesting ideas that might lead to a book. I was surprised and pleased and as soon as I received the prospectus guidelines from the editor, I got to work, describing my future book. In the prospectus, I started with the principles of multicultural education I had been thinking about for many years. I was especially concerned that much of what was being touted as “multicultural education” consisted of little more than celebrations of “ethnic” holidays and traditions, or depictions of famous people from heretofore-invisible groups in the schools’ curricula. Although this was a start in defining the field, I felt it was a feeble start. Acknowledging the significant role played by people and groups of diverse backgrounds in U.S. society was important, but it was not enough. Most discussions of diversity said relatively little about the sociopolitical context in schools and society that created educational inequality in the first place. As a result, “diversity” in and of itself did not usually address historic and longstanding issues such as racism, or economic inequality and exploitation. It was true that most theorists and academics in the field went beyond the “holidays and heroes” framework in their conceptualizations of multicultural education, but this more critical message was missing in most public schools and classrooms. I decided that Affirming Diversity would tackle this issue head-on. Thus, the sub-title “The sociopolitical context of multicultural education” was just as important as the title, “Affirming Diversity.” I never heard back from the editor who had come to see me, but within a month or two, I received a phone call from Naomi Silverman, at the time another education editor at Longman Publishers, who was interested in coming to Amherst to speak with me about my prospectus. At lunch a couple of weeks later, Naomi told me she had spoken to the education editor who had received my prospectus. Showing it to her, he said, “I thought something might come of this idea, but I don’t think so. Look,” he had said, rifling through the papers in his hand, “there’s no lesson plans. I don’t think it’ll work.” “Let me take a look at it,” Naomi offered. Fortunately for me, she did. Naomi understood from the beginning that I had no intention of writing a book with pre-packaged lesson plans. That would be as far removed from my idea of multicultural education, or any good education for that matter, as one could possibly get. As she read through the prospectus, Naomi began to see real promise in the ideas I had presented. Although it was to be a textbook, the proposed format and ideas led Naomi to suggest it could be a textbook different from others in that it would be a “critical, non-authoritarian textbook.” That was my idea as well. We became so excited talking about the possibilities for the book that two hours sped by. We finished our lunch, promising to be in touch as I continued to think about the book. I went home, re-wrote the prospectus and in a few days sent it to her. The rest, as they say, is history, or at least, my history.

In writing the prospectus, I felt that the principles underlying multicultural education should develop organically from the discussion of the sociopolitical context of education and society. I also wanted to give life to the meaning of diversity by including case studies of students of various backgrounds, ages, and experiences beyond those generally included in discussions of diversity, that is, African Americans and Latinos/as. I was enticed by the idea of using case studies, knowing it hadn’t been done before in a book on multicultural education. Besides African American, Latino/a, and American Indian, I also included White, biracial, Asian, Jewish, and Arab students, among others.I should mention that when Naomi asked several education scholars to review the prospectus, most had concerns about the use of case studies, believing they might solidify stereotypes about young people of particular backgrounds. Their reaction was understandable and, although I was still certain it was a good idea to include them, the reviewers’ cautions helped me pay close attention to how the case studies were crafted. I also asked other friends for counsel as I was preparing to write. I remember a dinner with friends one evening in San Francisco during an AERA conference. As was our custom for the first few years that I attended AERA, I was rooming with Patty Ramsey and Christine Bennett, good friends and scholars with books in multicultural education. They were eager to hear about my book and, although I had received some cautionary advice from others about using case studies in the book, Patty and Chris were enthusiastic supporters of the idea from the start. Whatever doubts I may have had about using case studies until that moment disappeared after we talked that night. As it turned out, the case studies became, and remain, the most popular feature of Affirming Diversity. James Banks, popularly known as “The Father of Multicultural Education,” was also instrumental in encouraging me. He and I had worked together on a couple of projects during the 1980s and one day as we met for coffee at a conference, he mentioned that he had seen my name in several “Acknowledgments” of other books. “Sonia,” he said, “I think it’s time you wrote your own book.” I was flattered but also a bit intimidated. I said jokingly, “But then my book will compete with yours!” He explained that we needed more high-quality books in order to build the field, and he was certain I could write such a book. He wasn’t afraid of the competition; in fact, he said, “The more the better!”

Shortly after receiving the contract from Longman, my family and I went to Madrid, Spain on my first sabbatical. Other than time with my husband’s family, I spent every possible moment either reading in preparation for writing, or writing. Each day as I sat at my computer for hours in our little extra-bedroom-turned-study, an endless stream of words hurled out of my head and onto the computer. It all seemed to be coming together: everything I had learned from my education, my teaching over many years, all the books and articles I had read, and all the ideas, great and small, I had thought and talked about with students, colleagues, and friends. A couple of years later, at the first book party after Affirming Diversity was published, someone asked, “How long did it take you to write your book?” My answer? “I could say it took two years, and that would be more or less accurate, but the real answer is, ‘My whole life,’ and that would be the truest answer.” Although my teaching career had started when I was 22 and my academic career when I was 29, it took years for me to write this, my first book. I started writing it in 1989 at the age of 45 and the book didn’t see the light of day until I was 48 years old. Affirming Diversity: The Sociopolitical Context of Multicultural Education made my career.

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

My initial reaction to the book was a combination of excitement and fear. Writing the book fulfilled a dream I had had for many years and in that sense, I was thrilled. But once one commits words to paper, the work is out of one’s hands. I was afraid to open up my first copy, fearful that I would find mistakes, or worse, discover I had written something silly, outrageous, or just wrong. It took me many days before I was able to open it, and by the time I read it, I was feeling pretty confident about it.

I received the first two copies of the book in the mail on December 7, 1991 (publication date, 1992) just as I was leaving the house to go to New York City to speak on a panel at a conference honoring Paulo Freire on his 75th birthday. I ripped open the package and grabbed a copy to take to the conference. When I arrived, I gave it to Paulo. I don’t know if he ever read it – he received so many books from his admirers – but for me, it was a significant gesture because although Paulo had never said or written anything directly about multicultural education, his thinking had an enormous influence on my ideas about it, and consequently, on how I have always envisioned and conceptualized it. |

||||||||||||

to return to the Books of the 20th Century Exhibition |

||||||||||||

an institutional member of the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience

Museumofed@gmail.com