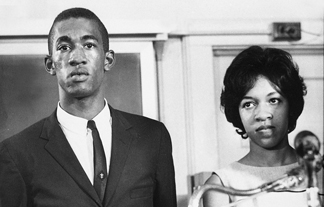

1963-2013: Desegregation—Integration “I was on the Debate Team with Robert and saw him as a person who was willing to break barriers. He knew what he was doing here and took his presence on campus very seriously, but he didn't take himself too seriously. He was strong and tough minded, smart and brash and certainly not subservient. He stood up straight and held himself in a manner portraying confidence and assurance. He was not going to sit in his room and be afraid of the university.” Thorne Compton |

|||||||||

|

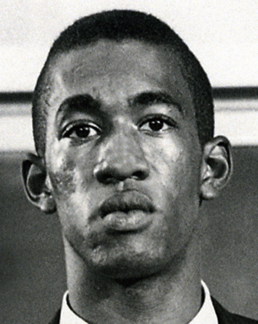

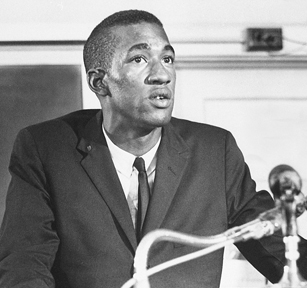

Robert (Bob) Anderson graduated from high school in Greenville and was enrolled at Atlanta University when applying, as a transfer student, to USC. When Robert Anderson received his official letter of acceptance on August 2, 1963, he became the first black student admitted to the University in the 20th century. (Henrie Monteith officially re-applied to the University on August 13, 1963.) |

||||||||

Robert Anderson was engaged in civil rights activities and worked closely with Martin Luther King, Jr. and other civil rights activists. After graduation from USC, he was drafted into the United States Army and served in combat during the Vietnam War. He returned from Vietnam and voiced his opposition to that war. Serving as a social worker in New York City throughout his professional career, Bob Anderson worked with the homeless and veterans of foreign wars.

“Coming to Carolina was the first experience of being impacted by racism. For many years I denied the impact of those experiences and those traumas. I remember walking across the Horseshoe, and there was a young man standing in the window with a broom stick. He said, ‘Nxxxxx, we’ve got you now.’ This is a memory that never left me, a symbol of what all the experiences meant to me. I hope that if we have learned anything, that no individual, no group, can be made to experience that kind of pain, that kind of trauma. And I think as individuals, as Southerners, and as Americans, we should cut out this cancer called racism.” Robert Anderson, as quoted in the November 21, 1988 Gamecock, republished in Carolina Voices, edited by C. B. Matalene and K. C. Reynolds, 2001, p. 179.

“Robert Anderson had a far more difficult time [at USC]. Like Monteith, he recalled that his life at Carolina was lonely and isolated. A Greenville native, he had grown up in a family and community that had protected him from prejudice; Carolina was his direct first experience with raw racism. ‘Some of my experiences at Carolina were funny, others painful, and some leave bitter memories and scars,’ he recalled twenty-five years later. He most often ate alone, and he commonly endured racial epithets from white students who would not confront him directly. . . . For the first month or so, white students would take turns bouncing a basketball outside his dorm room at night.”

“Robert lived on the Horseshoe and was in a room by himself (even though most students shared rooms). Ironically, a student who roomed near Robert committed suicide, an unfortunate incident having nothing to do with Robert. I knew this student and knew that he had a number of problems. The way Robert told the story to me, he mentioned that he returned to his dormitory and saw the police and university officials and knew that students were all talking and thinking that maybe he had died. Robert said that he could tell that the students were hoping that it was him.” Thorne Compton

“I didn’t live on campus, but during the early part of our first semester I would meet with Robert from time to time when I was on campus. Robert’s first year was tough. Students in his dormitory would come in at 2:00 and 3:00 am and would kick his door, yell an obscenity, and run. I told him that these students were cowards. Sometimes when we went to the Russell House to eat, students would stand to the side of a partly opened window and ask us if we had tails, or say something else like that. That is what he went through a lot of the time. James Solomon

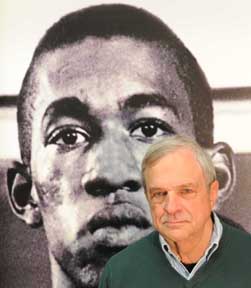

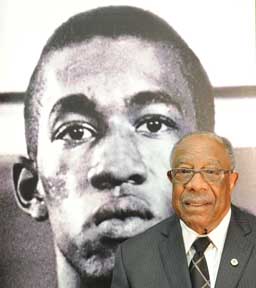

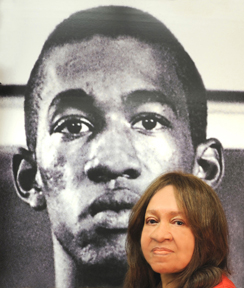

“At the 25th anniversary, we were invited back to the university and Robert returned. Everyone was very nice to us. Robert and I were walking over to the banquet and he said to me, ‘Jim, I’m so glad I came back. This changes my whole perspective of USC. I feel so much better about this school.’ When he left as an undergraduate, he told me he would never return. But during the end of that visit, he said that he was so glad that he had come back.” James Solomon

“Robert was a kind and gentle spirit who had every intention of breaking barriers at the University of South Carolina and in the world at large. He loved to play his horn and used music as a way of relaxing and enjoying genres that were not easily available to him once classes started and the rush to success began. Bob talked to me about the passive aggressive assaults that he endured at the hands of male students at USC. I recall his talking about people bouncing basketballs outside of his window all night so that he could not study and could not sleep. Others knew about the harassment; nothing changed. My family and I tried to provide some respite by having him spend a few nights now and then at the Simbeth Motel, owned and operated by my aunt, Modjeska Simkins. This move to the motel provided sleep for him but not relaxation or an opportunity to be around friends. The Simbeth Motel was a home away from home for many black musicians touring the South as there were few hotels that would accept them. Unfortunately not enough musicians were there during Bob’s visits to provide the blanket of friendship that he so sorely needed. I think back on my friend, Bob, and wonder what more I could have done. I was walking my own path, finding my way through the thicket. But that is no excuse for me or for those that silently stood by and watched the assault on a human spirit, the deferring of Bob’s dream. My friend needed advocates strong enough to stand up against those that persistently abraded his gentle spirit.

I think that even today Bob is still the canary in the coalmine for so many black men who are too often marginalized, ostracized, and ultimately shut away or shut out simply because of the color of their skin. I hope that those responsible for Bob’s turmoil have grown into better men who are now finding a way of reaching out to redeem the past. Until we face our past, our future will continue to be lived in dimly lit spaces where justice, peace, and democracy do not flourish and reign supreme. Then and now we need to step out of the shadows and praise the bravery of a man, Robert G. Anderson, Jr., who did the best that he could but whose strength and spirit were no match for the multitudes arrayed against him. I am glad that you were here, Bob. You are still here! Your spirit will guide many young men and women into the future just because you cared enough to take a stand for justice! Bob Anderson…GONE TOO SOON!” Henrie Monteith Treadwell

“Because of the experience at USC, Bob was very aware of racial differences but that didn't affect his relationships with people. He was loved by his veterans and the homeless men that he worked with—those who were black, white, purple, or pink. He was always able to see individuals and find their strengths. Bob was a true social worker. While he was qualified to be a clinician and could have enjoyed a lucrative private practice, that was not for him. He had a penchant for saving ‘wounded birds’ and hoped that, one day, they would be able to fly . . . or at least to hop around.” Susan R. Raskin

|

|||||||||

an institutional member of the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience

Museumofed@gmail.com