Cooperative Planning and Student Growth |

||||||||

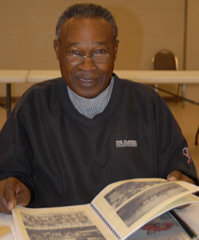

“The teachers instilled respect and kindness. Some were very sweet but they were also disciplinarians. We knew there was a line that we could not cross. But we also knew that they cared about us; they cared very much.” Otis Baker, a student during the time of the Secondary School Study

During the course of the Secondary School Study, Moultrie faculty lengthened the high school course period from forty-five to sixty minutes in what was an early form of block scheduling, conducted extra-curricular activities in an activities period during the school day, and developed a curriculum based on social problems (e.g., community housing or health) as determined by teachers and students (Moultrie High and Elementary School faculty, 1946, p. 20). |

||||||||

“The teachers were strict but we were not scared of them. We knew that they wanted us to do better in an unjust world. They never talked about civil rights and we were naive youth. But we knew we were being prepared for the world, and the teachers knew that we could make a place for ourselves.” Ira Thompson, IV, a student during the time of the Secondary School Study |

“Living in the South as a black . . . you knew it was a struggle. The teachers didn’t have to tell us that, and if they dared to step out of line, that would be the end of their jobs. We understood that. That’s the way it was—there was no other way . . . then. But they were preparing us for the future . . . for a different world.” Otis Baker, a student during the time of the Secondary School Study |

|||||||

The Moultrie faculty’s final 1946 report described their thoughts about the experimental process: “We see our school as a cooperative venture involving administrators, teachers, pupils, and parents, all working together in order to make life richer for all those concerned. The success of this process of working together, we feel, is regulated by the extent to which certain important working relationships are present in what we do. . . . We don’t try to teach lessons from books on relationships or have pupils recite lessons about desirable relationships. We try to make the relationships operate as pupils and teachers plan together, as pupils make reports or solve a problem in mathematics, as parent and teacher discuss the progress of a child or of work on some important community problems and as the faculty plans to carry out responsibilities in connection with the development of the program of the school—in fact, we try, as well as we know how, to cause the relationships, which we have set up as desirable, to operate in everything that we do. To us, discovering how to do, is just as important as knowing what to do. Knowing what to do does not always ensure a rich learning experience but knowing how leads to a program of action. We have known for a long time what to do about some things. For instance—‘Learn to do by doing.’ We even know why. We have read lots of the books which told us these things. But how to do! We had to explore that for ourselves and, once we got seriously started, it was exciting” (Moultrie High and Elementary School faculty, 1946, pp. 11-12).

|

||||||||

an institutional member of the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience

Museumofed@gmail.com